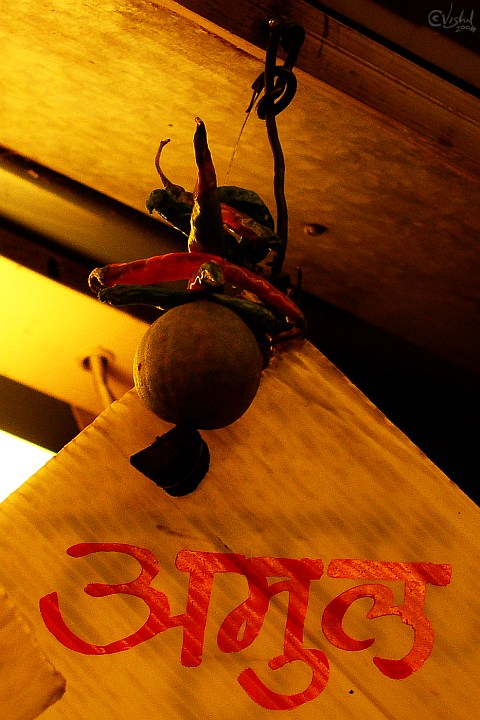

The lime, chillies and piece of charcoal hanging from a string is a charm used to ward off evil/bring good luck (to a business, especially). You’ll find them hanging at the threshold of even the most modern and trendy shops, and also under the front bumpers of goods trucks. I have seen it in use in domestic situations as well, though not as often as a string of mango leaves and flowers (usually marigolds).

The word underneath it, Amul (pronounced “uh-moul”) literally means “priceless” — it’s also a brand of butter and dairy products, and hence its presence on a sign at the top of a shop.

~

You know that joke, “I went to a fight and a hockey game broke out”? Well, I went to a war movie and a Lakshya broke out.

Lakshya (which rather coldly translates as ‘target’ or ‘aim’ — and doesn’t convey the emotional resonance the sanskrit word has) is the second film from director Farhan Akhtar (Dil Chahta Hai), and his first film not written by him (it’s written by his father, uber-lyricist Javed Akhtar). It’s mostly set in 1999, during the Kargil war, in which ‘terrorists’ (the majority of which were plain-clothes Pakistani army) infiltrated Indian territory and, well, tried to fuck with us.

We won.

Instead of being a broad, epic retelling of the actual events like J.P. Dutta’s LoC: Kargil (which had as many as 30 lead characters, not to mention their girlfriends and wives), Lakshya is a fictional account of a single soldier, Karan Shergill (Hrithik Roshan), in his pre-army days (where he’s an aimless urbanite) and during one mission of the Kargil war. It’s a coming of age story, much like Dil Chahta Hai; and also like DCH, it completely redefines its genre (for Hindi Mainstream Cinema, at least). It is, however, much more mature and subdued than DCH, and (perhaps its best quality) less filmi*.

Lakshya doesn’t follow any cinematic trend, or school; it’s simply Lakshya. The narrative takes its own time (the movie is over three hours long) but never seems slow; if anything, it seems to rush by too quickly. The battles scenes are not glorified at all; there’s no showdown between the hero and the main villain where they engage in a long, slow-motion fist-fight. The actual battle is a protracted, week long affair of attacks and retreats, lures and feints, and not a 20 minute gung-ho assault with a million men. The film isn’t about beating the bad guys and kicking sand in their face, it’s about reaching your goal, your lakshya. The love story between the hero and his sometimes girlfriend (Preity Zinta, playing a journalist) is not the usual cacophony of posturing and posing.

It’s a good story, well told, well acted, with lots of really good music (by Shankar/Ehsaan/Loy).

To say much more would ruin it, and so, if you can, do watch Lakshya. I think my brother said it best: “This is how war movies should be made.”

Oh, and I’ll ‘ruin it’ in the inevitable Post Mortem, which will be written after I’ve watched it again on DVD.

* Filmi: Indians use this term to define any unrealistic qualities of a film, i.e. the cinematic, dramatic stylization of events that happen in movies. I’ve seen the term ‘filmic’ being used by English-language reviewers, and while it’s close enough — like the word Lakshya — it doesn’t quite convey the emotion.