Last week I went to a couple of art exhibitions & a museum workshop, and they got me thinking about Art.

Now, I try to think about Art as little as possible, regard it from the corner of my eye, never cohere it in my inner ear. It’s the background noise to my chosen occupation that I dare not countenance lest it turn me into–ugh–an Artist. I’ve had to answer in the affirmative to the job descriptor ‘Artist’ a fair bit this past year, where earlier I used to go by ‘Designer’ and later, ‘Illustrator’ (it still says both of those things on my business card). But you draw one children’s picturebook, move countries to a place nobody knows you for anything else, and suddenly it just becomes easier than saying, “Well, it’s hard to explain. Generally I’m a graphic designer who has done everything from print to interaction but now I’m blah de blah de doodly whocares…”

Artist.

Give the people what they want. You draw, you’re an Artist. Only, I started to wonder, because there’s a bunch of people out there, people who draw a bit like me, who steadfastly go by ‘Illustrator’ and even ‘Graphic Artist.’ Who the hell are they, and am I one of them? I had enough of a hard time wondering if an old fart like me, who knew what an ICC Profile is and who hand-coded CSS, should describe himself as a Graphic Designer in the age of UX & UI ‘Storytellers.’ Now I was supposed to split hairs because I might be vaguely questioning the tenets of conversation that interrogate the lacuna between digital space & Indian truck graphics? Isn’t that what Graphic Artists do, grow beards and make faux vintage travel posters about Mulund?

I went to the opening of a show by an artist I’ve seen mentioned previously as an Illustrator and whose work shares spaces & shopfronts with Graphic Artists. Sameer Kulavoor’s show, “A Man of the Crowd” is well worth the trip to TARQ gallery in Dhanraj Mahal (it’s on the way to Gateway of India), as pictures do not convey the texture of the canvasses. In person you can lose yourself in the scenes of seemingly ordinary street life, delight as your eye catches on details, picks up on sudden invasions of the surreal, the fleeting feelings of deja vu as you wonder if you’ve seen all of these crowds, these people, before, and you will again.

And then there are the little figures peppered through the gallery, like a scavenger hunt. It’s an exhibit of some whimsy, and while I’m sure it might translate to the Graphic Artist and Illustrator realms of the print, the postcard, the regulation coffee mug (that’s too big for anything except conversations about cool coffee mugs), it remains a work of in-person engagement for me. An Artist thing. If art is supposed to make you feel something, then it did make me feel nice for a while.

Two days later I had a much different reaction to an exhibition.

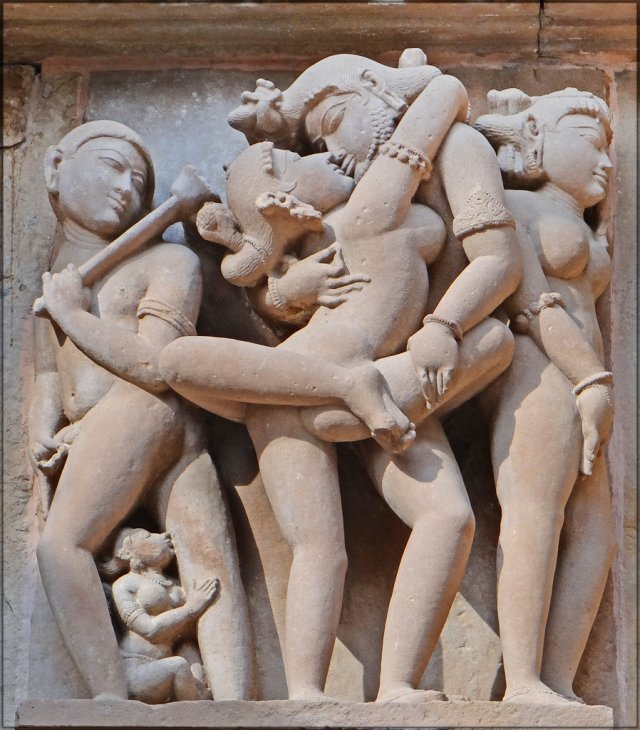

In between that, though, immediately after A Man of the Crowd, I was literally in a crowd, heading up to Goregaon in a fast train. There’s no artistic significance to this except that for a good while my body was contorted in a position for which I have found a suitable analogue:

…So yeah, like that, only with negative thirty-seven sexiness. Negative thirty-seven-point-two, even.

In Goregaon I rose up a tower to a friend’s place, where I was requested to BYOB and bring something sweet, and between the train & the gallery I could only think of popping into a supermarket and raiding the sweets aisle for anything colourful. This turned out to be an excellent idea in a party filled with happy-making substances (I brought rum) and chicken biryani. Sour Strips go very well with whiskey, apparently. Strawberry & Cream lollipops are amazing at 2AM, unpaired. And when someone discovered that the packet they came in had a bunch of transfer-on tattoos, well, everyone had to choose one face-down and pick a spot on their body to have it.

A tiger tattoo you get in a lollipop pack is not Art, but at 2AM with rum & biryani in my belly and the company of many smart, funny, joyously inquisitive friends, it might well have been a certain kind of art. Staring at it, my mind flashed back to a corner of one of Sameer Kulavoor’s canvasses. A tiger, leaping off the frame, only its hindquarters and tail to be seen. Art is in the connections. Art is in the feeling you get, both from it, and later, when it isn’t there.

A day passed in work and prep, and then I found myself at the museum, good old CSMV as they’re lately calling it, in the role of none of the aforementioned things, but that of an Assistant to Samir who was doing a workshop on papercraft.

Samir’s done three of these workshops so far, each wildly different, but all paper-based. He has taken to describing himself as a Paper Artist, and deservedly so. But as two process-fiends with design backgrounds and cold, clockwork hearts, we are of a similar approach to some aspects of the Art. His workshops bestow technique, give pupils a leg up and often a significant leap from zero to adept paper artists themselves, but rarely does he get into the philosophy, the sentiment, the driving force that Art often strives for. He’ll tell you how to bend a quilled paper strip around a corner, but what someone is supposed to feel about that bend is up to them.

Nevertheless what came from this workshop was a variety of expressions, from perfectly quilled mazes to wild abstract shapes that vaulted off the delicate paper pots. It surprised both of us.

A similar event was thrust upon to me last month, when my friend & author of that book what I done draw, Raja Sen, couldn’t make it to a talk we were supposed to give at the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival. What was supposed to be 45 minutes of Uncle Raja reading the book out to the assembled target audience of munchkins and Uncle Vishal providing occasional banter and 10 minutes of doodling on a whiteboard, turned into a solid hour of me fumbling with a microphone, sweating profusely in a jacket, and scraping the confines of my brain for some metaphor about how to draw cartoon animals that 10-year-olds would understand instead of, “lay down volumes through the use of construction lines and basic solids.”

I settled, somewhere in there, on what I called, “The Three Potato Method.” It may have worked. I realised later, coming down from the nervous adrenaline, that it was literally the first time I’d got up in front of a crowd of any size to teach something, let alone Art. It’s a blur, but somewhere in there I recall at least gesturing towards meaning and feeling in drawing, but mostly I stuck to imparting technique. I have no idea how much of it landed, unlike with Samir’s quilled pots.

My father says I did really well. My mother would probably be more objective about the whole event, but she’s dead.

Manu Parekh has been producing Art for longer than my mother was alive, a fact that beamed loudly (but not with that personal connection) from the posters that had been thrown up around the NGMA. We wandered in after the workshop, stuffing a bag full of leftover paper things and extra materials into their lockers. I go to the NGMA as much to see the building as any art in it. It’s a bonkers space of ascending levels capped off with a domed space where every footstep pings off the boards like science fiction sonics. Ken Adam & Kubrick would have loved it. It’s also an intimidating space, none of the avuncular can-do of the Jehangir, so to fill it with just one artist takes quite some Art, and quite some Artist.

Parekh’s headline pieces took up the middle tiers, where the wide canvasses could fully spread their wings. Varanasi emerged in several forms, best of them in this tangle of black & white. A point-and-click adventure game background via the heptapods from Arrival. Throughout the 60-year retrospective: eyes, eyes, big and small, sometimes actually stuck to the canvasses in the form of little teardrops with pink corners and blue-black irises. Crowds of them.

But the thing that upset me was right past the entrance, in the first ’round’ of space before the stairs. And it upset me because most people went past it without half a glance. On one wall was a series of small works, the biggest around a half imperial, in a range of styles & subjects, many from the 60s, many switching styles wildly within the same year. One, high up, a tidy collection of curved strokes seemed to cohere into a face, but could well have been a letter scribbled with many a flourish. It deserved its own wall, but there it was up in a corner above the eyelines of most people walking past.

And right opposite, were the sketchbooks. Enormous, full Imperial size tomes, four of them, laid open on stands, for anyone to flip through. And I did, through every page of every one, because I don’t care where you stand on the scale of technician to Illustrator to Graphic Artist to Artist, if someone gives you a chance to look at their sketchbook, you look. And there it all was: the eyes, the Varanasi ghats, the recurring figure eights, the typographical marks that said nothing in no language other than that they exist, page after page until, like minor drawing fiddlers like myself, the artist got bored or took a fancy to newer, sexier paper, and abandoned the book with a hundred pages blank.

Art is supposed to make you feel. Art is supposed to move you, upset you, confuse you, frustrate you. It’s often enough that it entertains you, that it makes you chuckle. It’s the tail of a tiger, the head on your forearm, lollipop tattoo and burning bright price tag. It’s a canvas the size of your apartment and your neighbour’s, in Bombay, that you take a selfie in front of, right next to a “STRICTLY NO PHOTOGRAPHY” sign. It’s minuscule squeezes against wood floors that echo large as you dance politely in Ken Adam strokes across the dome.

But art is also process. It’s sitting down or standing up, with pencil and brush and whatever, and putting down the marks that make the work, and the marks that make you. It’s giving an occasional page to a child, a whole Imperial cold pressed acid-free 350gsm page, to let them draw what turns out to be an eerily sinister forest scene where someone from a cabin mouths “HEELp” and on the next page, you get back to portraits.

As I headed for the door, a crowd was gathering at the foyer. Manu Parekh himself was due to do a walkthrough in a short while, and art lovers milled around waiting, safely shielded from the art until the appropriate moment. Upstairs in the dome, chairs were being set up in neat rows with neat plinks and twangs off the floorboards. I considered waiting, folding into the South Bombay society ladies, maybe ask about where he got those enormous sketchbooks (Commissioned? Some tiny shop in Bora Bazaar? Surely not Amazon?), or ask about that one study in blue that wasn’t on its own wall. I didn’t stay.

I hate crowds.